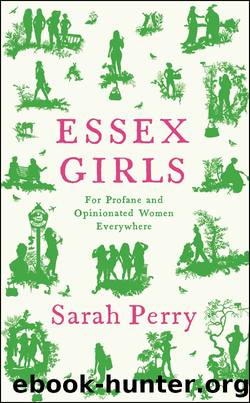

Essex Girls by Sarah Perry

Author:Sarah Perry

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Profile

Published: 2020-11-15T00:00:00+00:00

6

IN JUNE 1840, in Londonâs Exeter Hall, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society held the World Abolition Conference, and devoted much of the first dayâs proceedings not to the question of the emancipation of enslaved people, but to whether or not women should be permitted to attend as delegates. The official report of the convention notes that in the end âthe upper end and one side of the room were appropriated to the ladies, of whom a considerable number were presentâ. When Benjamin Robert Haydon completed his painting commemorating the event the following year â positioning the abolitionist and emancipated slave Henry Beckford in the centre of the foreground â he included, towards the far right of the immense canvas, a group of six women, and among them, in a lace-edged bonnet, was the Essex girl Anne Knight.

She was in fact a Chelmsford girl, born to a grocer in 1786. She was a Quaker, which was and remains in its way a radical identity, with a commitment to equality, peace and social justice being more a less a tenet of the faith. In 1825, she joined the Chelmsford Ladies Anti-Slavery Society, and â being fluent in both German and French â travelled Europe in the company of other Quaker women, attending to various charitable causes: a Grand Tour for the politically conscious.viii She was an indefatigable correspondent, covering sheets of paper in a large and looping scrawl, and something of a difficult dinner guest, on occasion wearing a silk bag attached to her belt, and reaching into it to withdraw pamphlets should she encounter a political opponent in need of correction and reproof. Deploring the treatment of women by the leaders of the Chartist movement, she wrote with brisk disfavour that for them âthe class struggle took precedence over womenâs rightsâ. Writing of the inability of women to vote in national elections (at that time women of a certain financial standing could vote in local political elections), she said: âI am forbidden to vote for the man who inflicts the laws I am compelled to obey â the taxes I am compelled to pay â taxation without representation is tyranny.â Notwithstanding the urgency with which she felt her disenfranchisement, it is vital to understand that she did not define the nature of her womanhood by the ways in which that nature was repressed. She did not so much chafe against the constraints of her gender, as refuse to feel the constriction: âWe are not the same beings as fifty years ago;â she said: âno longer âsit by the fire and spinâ, or distil rosemary and lavender for poor neighbours.â That conventional womanhood prevented her peers from doing their duty as citizens infuriated her: when her friend Maria Chapman was unable to attend the abolition conference, she bemoaned the other womanâs married state, which had doubtless led to her absenting herself from the cause of justice. âAh, that thou hadst not married!â she wrote. âThat thy âproper sphereâ at this juncture

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Blood and Oil by Bradley Hope(1558)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1407)

Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte by Kate Williams(1380)

Daniel Holmes: A Memoir From Malta's Prison: From a cage, on a rock, in a puddle... by Daniel Holmes(1324)

Twelve Caesars by Mary Beard(1310)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1291)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1165)

What Really Happened: The Death of Hitler by Robert J. Hutchinson(1154)

London in the Twentieth Century by Jerry White(1141)

The Japanese by Christopher Harding(1129)

Time of the Magicians by Wolfram Eilenberger(1121)

Twilight of the Gods by Ian W. Toll(1110)

Cleopatra by Alberto Angela(1091)

A Woman by Sibilla Aleramo(1089)

Lenin: A Biography by Robert Service(1071)

John (Penguin Monarchs) by Nicholas Vincent(1062)

Reading for Life by Philip Davis(1023)

The Devil You Know by Charles M. Blow(1018)

The Life of William Faulkner by Carl Rollyson(976)